Relationship of political ideology of US federal and state elected officials and key COVID pandemic outcomes

Now that our paper is out in the Lancet Regional Health Americas, I wanted to write up a blog post talking about it.

Our paper is available free and open access here: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanam/article/PIIS2667-193X(22)00201-0/fulltext

One of the main contributions this paper makes is that it considers above and beyond the voter lean of the public what the impact of political ideology of US House and Senate representatives may have been during the first year in which vaccines were widely available for adults (April 2021–March 2022).

Part of what made this work possible was having the data available on Congressional representative’s political ideology/leaning available from Voteview.com which applies a principle components analysis type approach to Congressional representatives’ votes on individual bills. This allowed us to incorporate information not just on whether representatives were Republican or Democratic, but the degree to which they leaned Republican or Democratic.

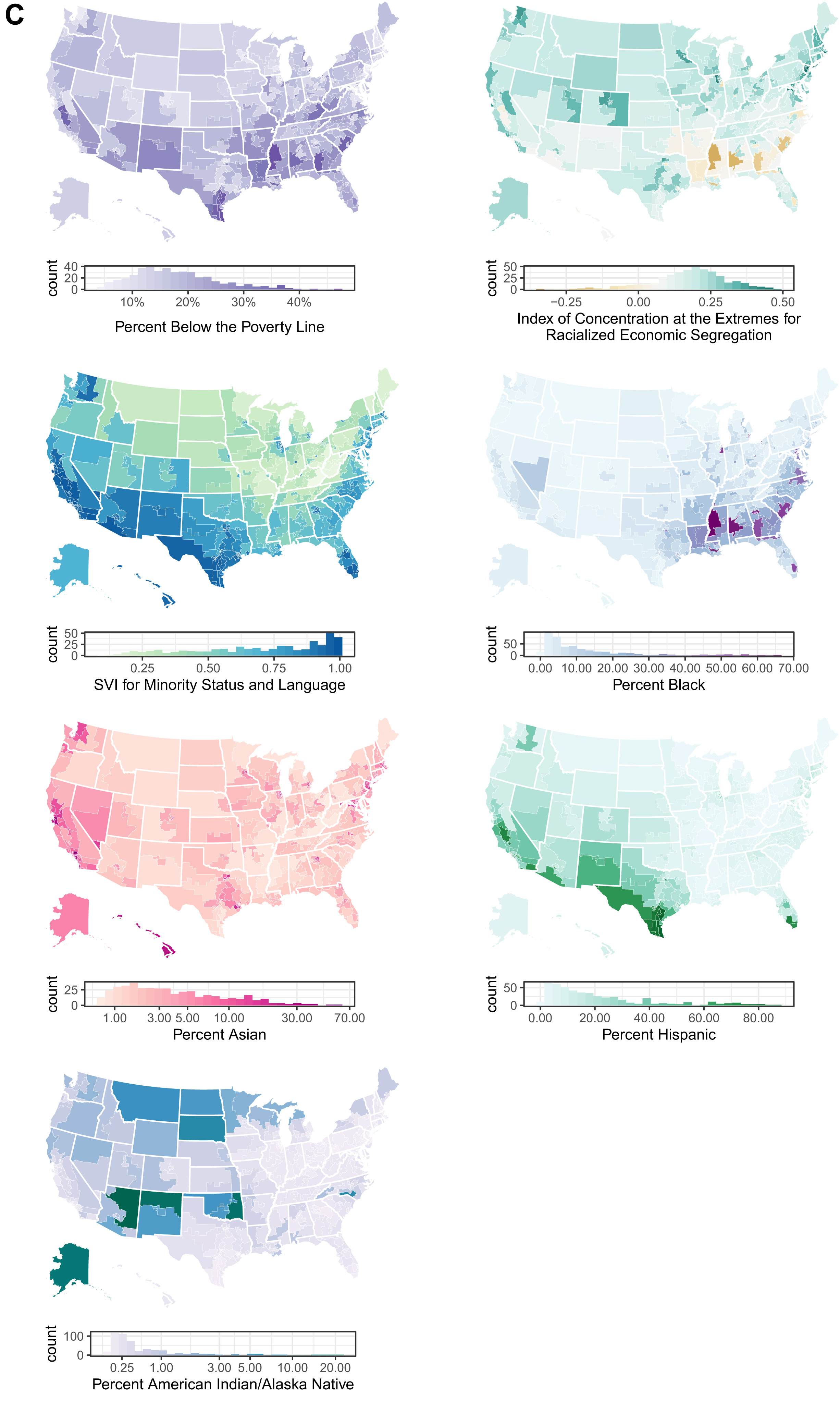

We included a quite substantial list of county level covariates, described fully in the captions to our figures in the article. Click on the below images to see the full resolution versions.

|

|

|

|

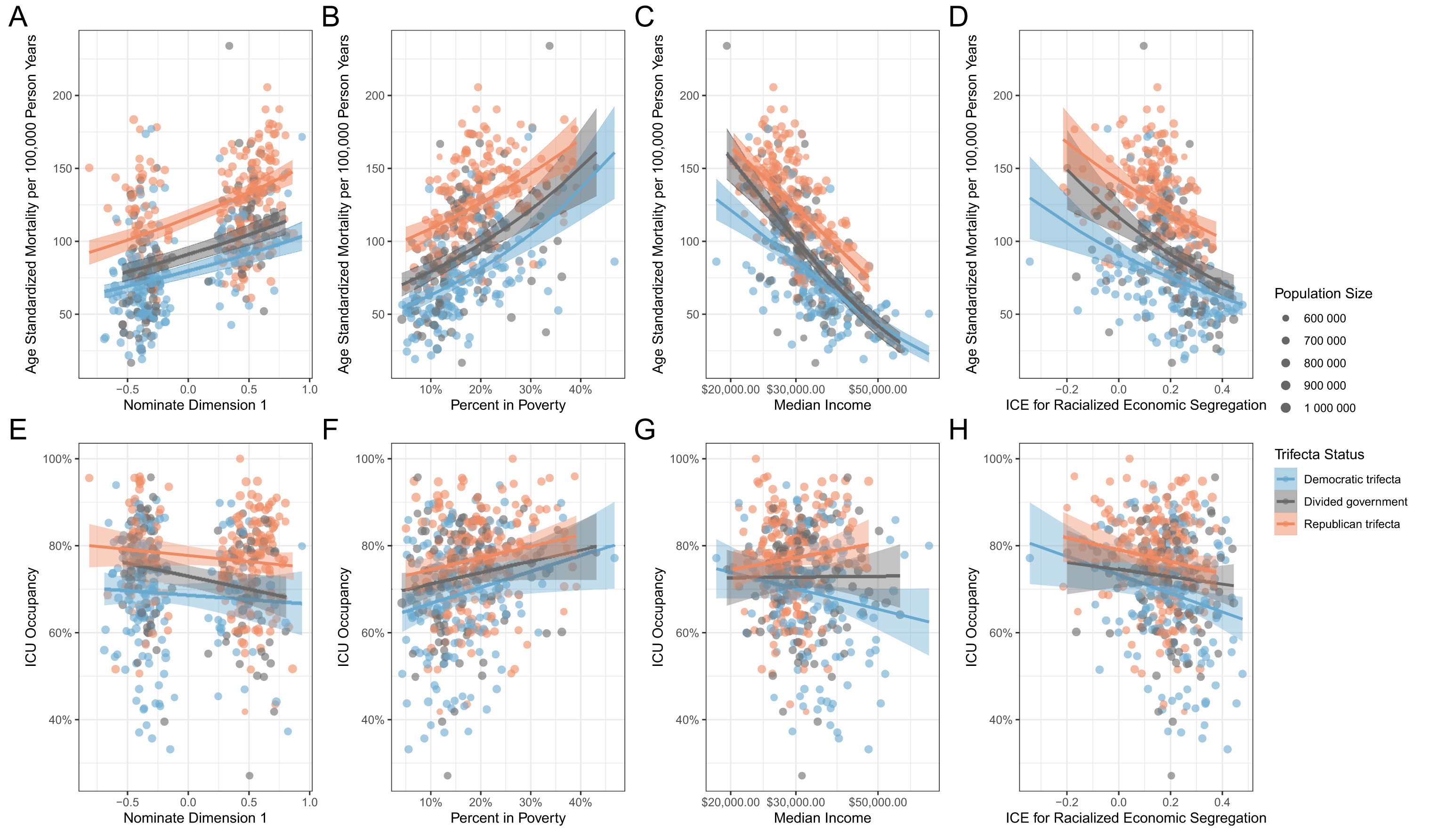

Figure 2 depicted the bivariate relationships between COVID-19 mortality, ICU capacity, and several of our most important covariates stratified by state trifecta status (i.e., whether the House, Senate, and Governorship were all controlled by the same party or divided).

Figures 3 and 4 showed how various political ideology metrics were associated with our outcomes of interest either in univariate relationships (model 1), after adjusting for demographic and social metrics (like median age, log population density, percent below poverty, the Index of Concentration at the Extremes for Racialized Economic Segregation, and racial/ethnic composition) (model 2), after additionally adjusting for all of the other political metrics (model 3), after further adjusting for vaccination (model 4), and after adjusting for risk factors like the percent with obesity and diagnosed with diabetes (model 5). Essentially this follows the logic of starting out with an un-adjusted analysis that compares the outcomes (age standardized COVID-19 mortality and ICU occupancy) with each of the political metrics one-at-a-time in model 1 and then adds on additional variables sequentially going from model 2 to 5 to illustrate how much of the effect associated with political ideology may be explained by associations with other measured factors.

One of the things that I think is so great about this paper is that it provides an almost perfect followup to some of our previous work, The Evolving Roles of US Political Partisanship and Social Vulnerability in the COVID-19 Pandemic from February 2020 - February 2021 both in terms of the subject-matter of focus and the time-periods being studied. I think it’s particularly nice that we were able to study the February 2020-February 2021 time-period as a timeframe during which trends in the pandemic were largely driven by factors unrelated to vaccination, and to follow that up with a separate paper focused on March 2021-April 2022 when vaccines were a much larger part of the picture.

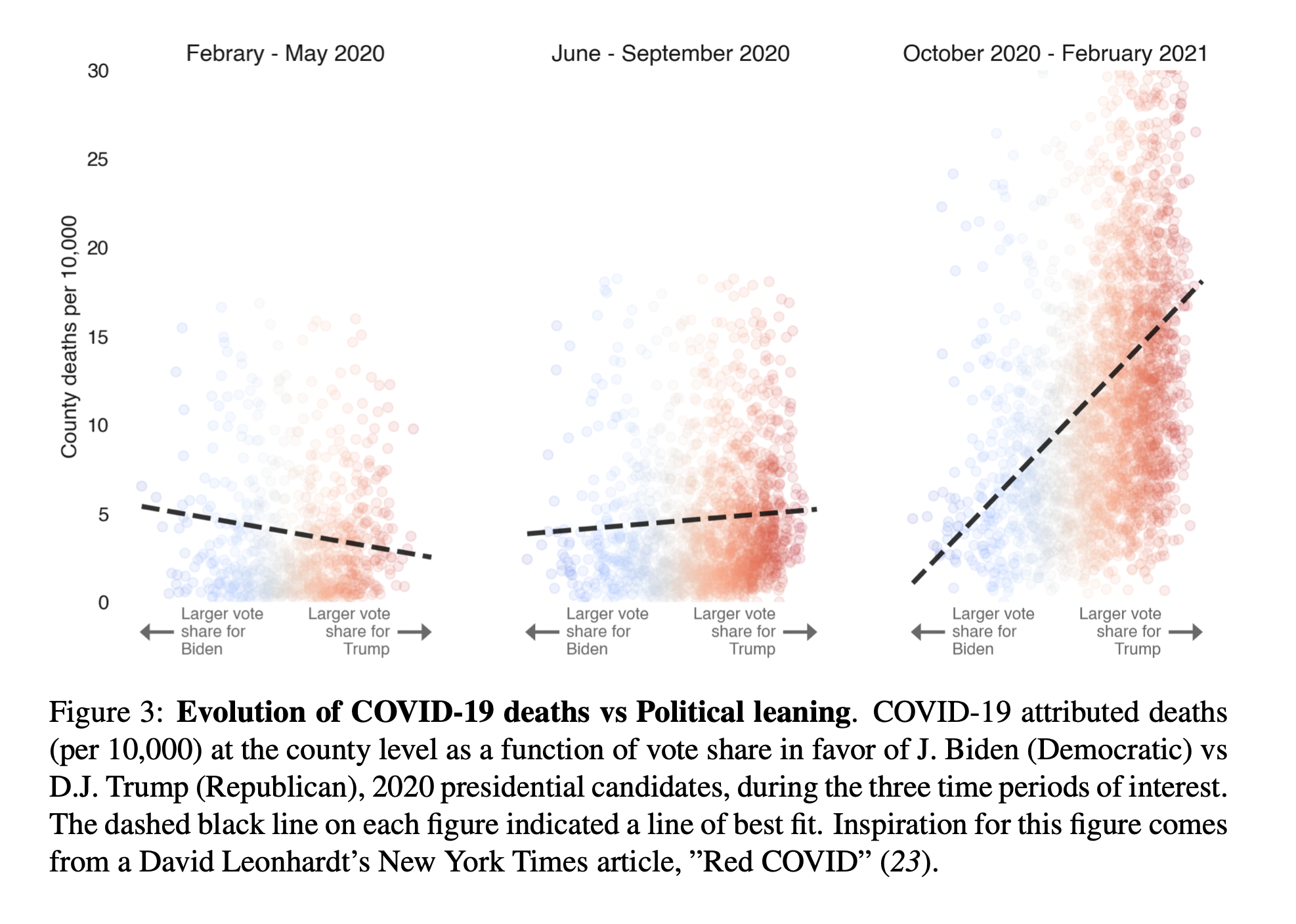

In that paper we put much more emphasis on the role of voter lean (as in the political lean of the population residing within each county) rather than the political lean of representatives. For example, figure 3 from that paper drove home the point that the relationship between voter lean and COVID-19 mortality was changing as the pandemic progressed.

This blog post isn’t about that paper, but I think the two papers are worth reading together.

One final word on this is that I’d just like to say it’s been extremely gratifying seeing our work pay off. At one point the press release written about our article was on the cover of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health website, and our article appears at the top of the list in the Most Read articles of the Lancet Regional Health Americas. Publicity isn’t everything, but it’s nice to see that our article is reaching a wide audience and hopefully advancing thought on the political determinants of public health.

Once again, the links to these two articles:

- Relationship of political ideology of US federal and state elected officials and key COVID pandemic outcomes following vaccine rollout to adults: April 2021–March 2022

- The Evolving Roles of US Political Partisanship and Social Vulnerability in the COVID-19 Pandemic from February 2020 - February 2021